| Botswana National Report Summary |

| 2002-2003 |

| Prepared by Faith |

|

the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reported that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions were the highest in history and that the impacts on human and natural systems are widespread the world over (IPCC, 2014b). It reported a warming trend across the African continent

![]()

![]()

| _ |

|

Botswana’s developmental agenda is driven by its current 20-year national visioning - Botswana’s Vision 2036. The country’s Vision 2036 is aligned with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as well as with the SADC Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan (RISDP). The country’s natural capital is vital to both its economy and wellbeing of its people. The government made a promise of ‘prosperity for all’, through the Vision 2036, to transform the country from a middle-income into a high-income one. The country has pegged its SDG implementation to its Vision 2036, thus formalizing and institutionalizing the achievement of the SDGs. To ensure positive outcomes it will be necessary for the country to embrace policy adjustments, changes in habits. For instance, and in line with the SDGs, Botswana’s Vision 2036 seeks to transform the country into a high-income nation as part of efforts to address poverty. The Vision 2036 is also linked to the RISDP whose objective is to deepen regional integration in Southern Africa by accelerating poverty eradication, creating a common market, ensuring food security, and managing transboundary resources. To deliver on its sustainable development agenda and Vision 2036, Botswana continues to strengthen its governance systems, including building strong institutions to manage public resources. It also continues to preserve traditional local institutions, which are centred around morafe (chiefdoms) and administered by dikgosi (chief), thus complementing the formal administrative systems. The blend of traditional and elected governance systems is key in the orderly delegation of authority from central government to districts and local institutions, especially in the natural resources management, including sustainable management of land and water resources. At the regional and sub-regional level, Botswana aligns itself to the norms and standard of the African Union and Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), respectively. For instance, its policy landscape and general state of the environment are also guided by the shared nature of resources, as well as regional policy instruments such as the SADC Revised Protocol on Shared Watercourse Systems. At the national level, the country’s Ministry of Environment and Tourism has the mandate for managing the balance between development and environment in Botswana. Through its various departments and instruments, it brings together issues that consider economic development and environmental stability and the sustainable management and utilization of its natural resources. Botswana’s national legislative instruments relevant to the environment sector include Tourism Act, 1990, Wildlife Conservation and National Parks Act 1992, Waste Management Act 1998, Environment Assessment Act 2011, among others.

|

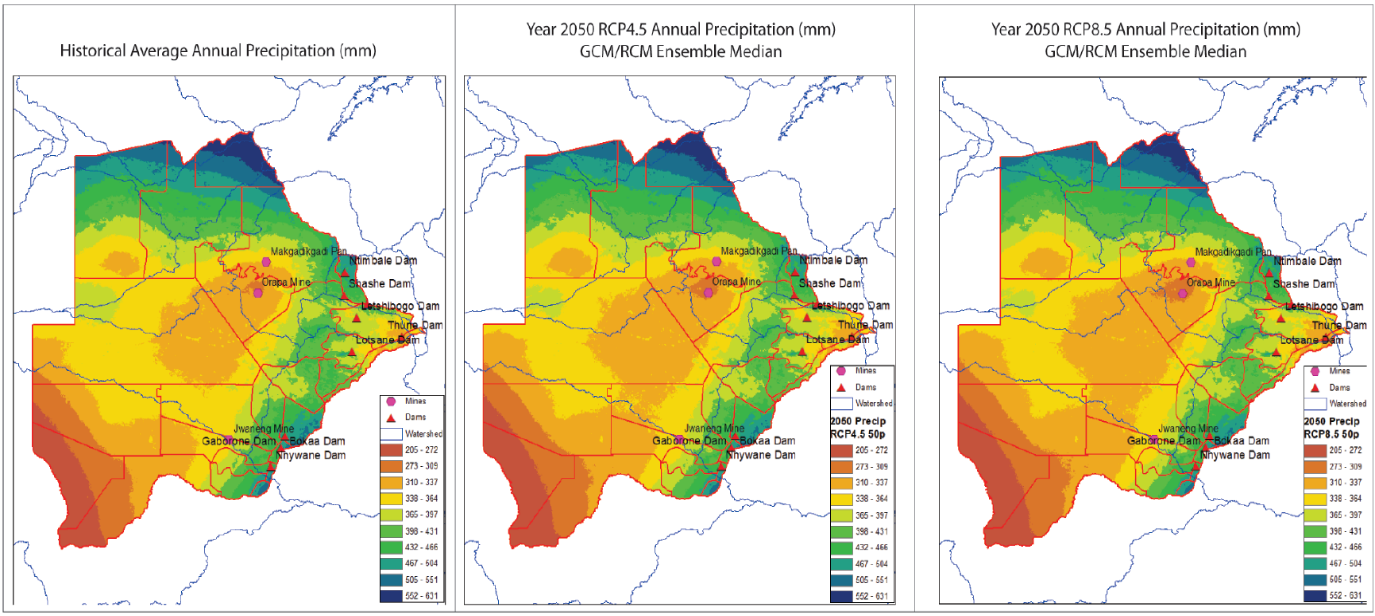

In Botswana, climate change manifests itself in the form of increased variability of key climate elements such as temperature and rainfall, and through an increase in the frequency and severity of extreme events such as heat waves, destructive rainfall, flash floods, and droughts. The main concerns for Botswana are increased energy and water stress because of rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns, losses in rangeland productivity and reduced agricultural yields which are profoundly threatening food security. UNEP reports of 2021 on Botswana’s state of environment for temperature trends over the last several decades indicate that it has experienced a considerable increase in temperature over recent years. An analysis of climate data from 1970 to 2015, for instance, shows an average rise of temperature by around 1.5°C. Rainfall is highly variable in time and space. Rainfall variability is an important feature of semi-arid climates, and climate change is likely to increase that variability in many of the regions of Botswana. The average annual rainfall for Botswana is approximately 405 mm, while the mean number of wet days is around 53. Trends for annual average rainfall across Botswana indicate a general decline (Nkemelang et al., 2018). Projections from Botswana’s Ministry of Environment and Tourism shows by 2050, most of the country will experience high average temperatures of 25°C to 26.9°C, thus the country will be hotter than relative baseline temperatures. Figure 3 and 4 illustrates historical annual mean temperatures and temperature projections for 2050 using Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) values - RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5.

![]()

![]()

| _ |

|

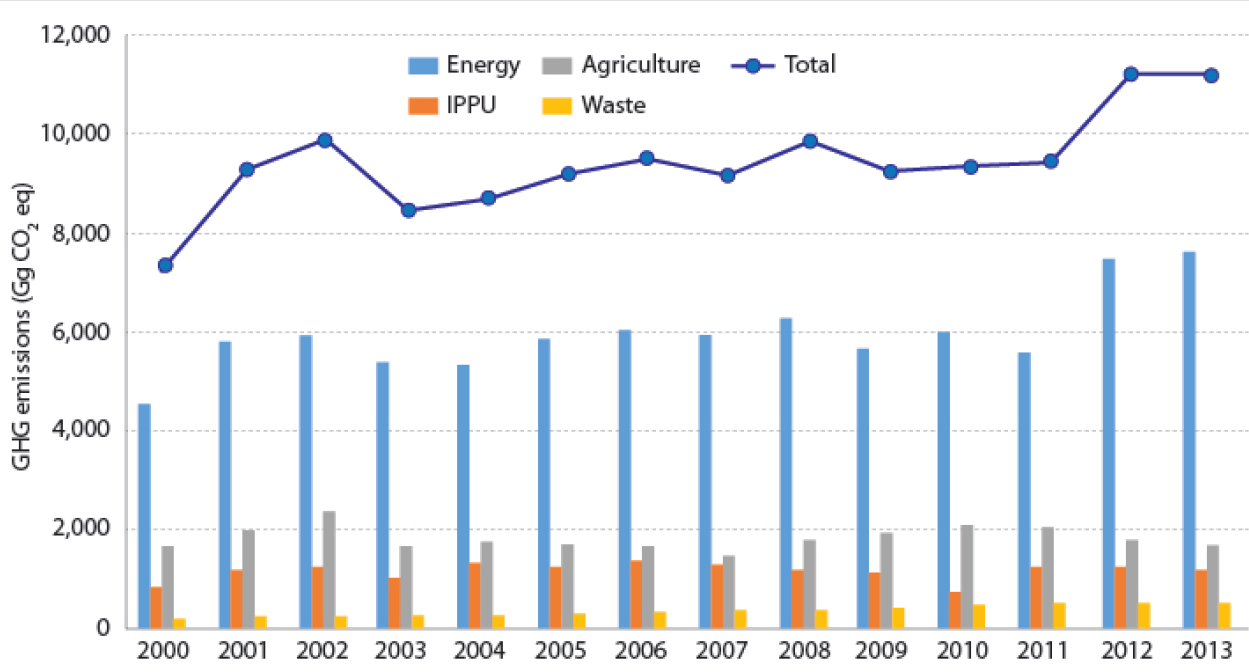

Botswana, being a climate-stressed country, small increments in global mean temperature have serious societal consequences that will demand progressively more radical adaptation responses. Such climatic shifts present a growing adaptation challenge between 1.5°C and 2.0°C for key economic sectors in the country. The country’s huge reliance on rain-fed agriculture and natural soil fertility continues to heighten its vulnerability to the changing climatic situations resulting in food insecurity and poverty, especially in areas with dryland farming enterprises. Large development activities such as clearing for settlements, industrial activities and commercial agriculture may also have a negative impact on the environment resulting in habitat loss, deforestation and ultimately land degradation, which cumulatively weaken its ability to combat the impacts of climate change. For instance, the doubling of land used to grow crops during the Integrated Support Programme for Arable Agriculture Development (ISPAAD) project in 2008 is thought to have encroached onto fallow and virgin land with potential impacts to soil and biodiversity. At the same time, Botswana is already water-stressed, with projected cuts in mean annual rainfall, as well increased length of dry spells. These situations are set to escalate stress, leading to more frequent water shortages in Botswana’s urban and agricultural supply systems. Locally, Botswana is also struggling to contain its local greenhouse gas emissions (GHG). Governmental reports show, in 2015, the country’s GHG emissions stood at 9310.72 Gg CO2 eq. from Energy, 1221.69 Gg CO2 eq. from Industrial Production and Product Use (IPPU), 644.42 Gg CO2 eq. from Waste and -947.94 Gg CO2 eq. from the Agriculture, Forestry and Land-Use (AFOLU) sectors. The net emissions after accounting for the removal was 10,228.89 Gg CO2 eq. It thus emerges that the country’s energy sector continues to be the largest source of local emission, accounting for 91 per cent of total emissions (including AFOLU) and 83 per cent emissions without AFOLU.

![]()

![]()

| _ |

|

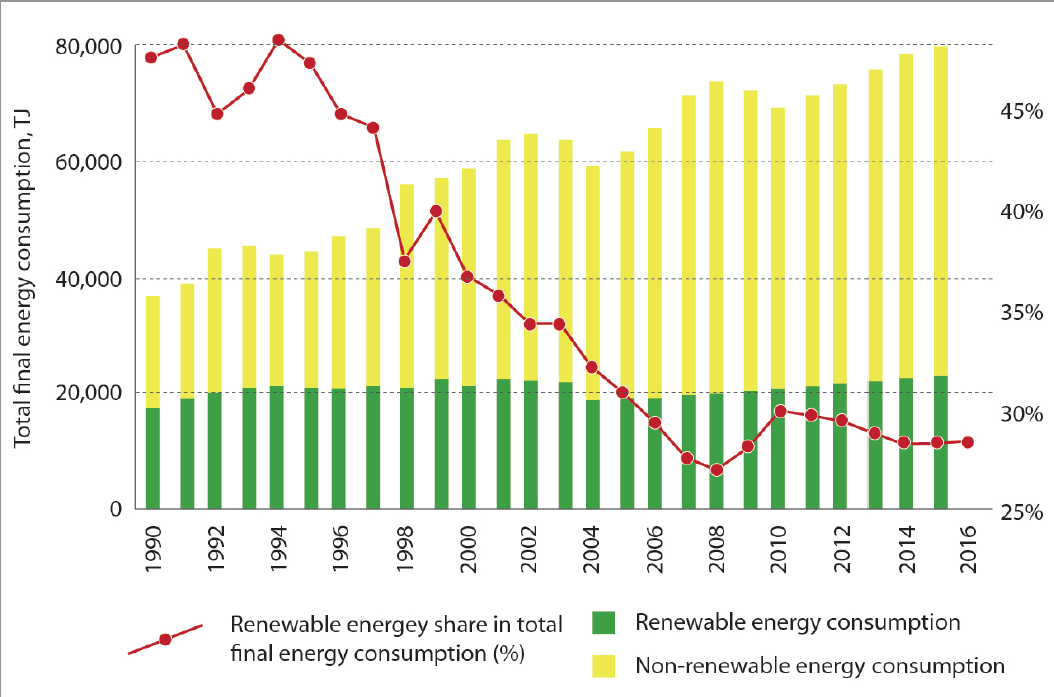

Botswana continues to prioritize adaptation as frontline response for climate change. Presently, sectors vulnerable to climate change impacts are promoting and implementing various adaptation measures. The country’s water sector, for instance, is focusing on the construction of pipelines and connections to existing ones to transmit water to demand centres. This is being paired with investments in a telemetric monitoring system with a view to reduce water loss during transmission, as well as enhancement of conjunctive groundwater-surface water use. In the agricultural front the country is working on measures for the improvement of genetic characteristics of livestock such as Musi breed. In addition to this, are targeted interventions for improving livestock diet through supplementary feeding, and diversification of crop varieties and technologies. On the climate mitigation front, Botswana continues to broaden its clean energy interventions. The country envisions measures such as biogas plants, solar power stations, streetlights, solar-powered boreholes, solar geysers, and air monitoring systems as some of the priorities for mitigating emissions from its energy sector. As of 2019, Botswana’s national access to electricity stood at 70 per cent, though the access rates vary highly between the urban and rural populations. United Nations country reports show the rate of access to electricity among the country’s urban population was 88 per cent in 2019, and 28 per cent for the rural areas, in the same year. At the local level, the country has also attempted to reduce the electricity losses through some initiatives at household level, such as replacement of incandescent bulbs with compact fluorescent bulbs (CFLs) in selected households. This was an initiative implemented by BPC in 2012, aimed at reducing electricity consumption through demand-side management. This initiative resulted in an average national demand reduction of 33.5 MW at the time. However, this strategy was not sustained as users reverted to the use of cheaper incandescent bulbs for replacements afterwards. On policy interventions, Botswana’s Government has developed some energy management statutory documents, aimed at streamlining its guidelines and regulations for the implementation of energy efficiency measures across all energy consuming sectors. It is hoped that this will aid in sustaining and avoiding premature failure of energy efficiency initiatives as was the case with the BPC roll out of 1,000 CFLs in households in 2012. These statutory measures include those on national building control regulation and energy management standards.

![]()

![]()

| _ |

|

The global nature of climate change forces Botswana to invest more on adaptation than on mitigation. With the water sector greatly affected by the rise in temperature and increase in mid-season droughts, Botswana has an opportunity to ramp up targeted investments in integrated water management systems. Such interventions should consider the ecosystems on which the sustainability of water availability and supply are anchored on. This includes wide-ranging policy and regulatory interventions for both the surface and underground freshwater resources, as well as smart water harvesting systems in both its urban and rural areas, all of which should be compatible to current and anticipated climatic scenarios. Additionally, and with the country’s rural villages remaining poorly electrified, there is opportunity for SMART Mini Grid-based electrification given the scope and success of the PV systems. These Smart Mini Grids could include smart futures after practical considerations. Since most of the areas receive ample sunlight, Solar PV models can be chosen in conjunction with biomass.

|

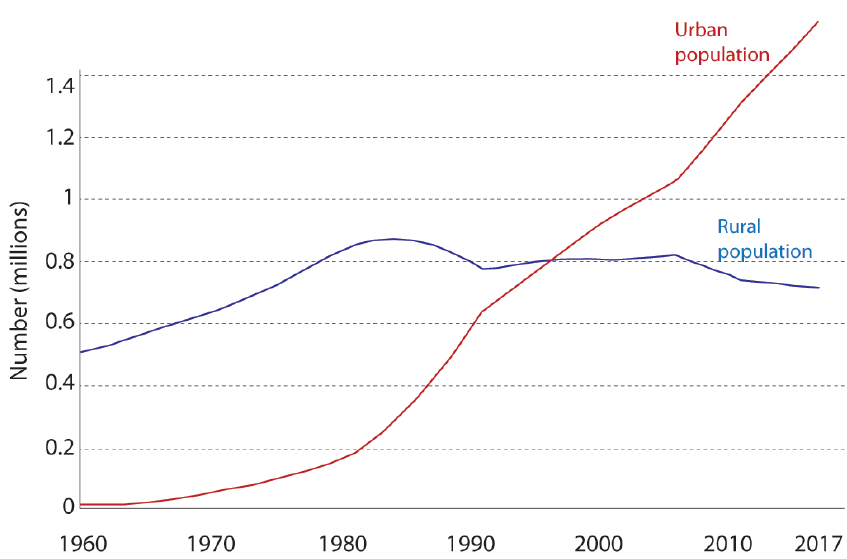

Pollution and waste remain a big challenge in Botswana. This growing twin problem is mainly shaped by many socio-economic factors that include increasing populations and urbanization, as well as mining and establishment of big infrastructure projects. Presently, for instance, national reports are showing a continued surge in the amount of electronic waste, with the UN statistics of 2020 documenting rise from a per capita average of 2.83 kg per year in 2000 to 7.92 kg per year in 2019. These figures are expected to bulge going into 2030. Similarly, hospital waste, which averages 0.1 kg to 0.75 kg per patient, according to UN reports, is another hazardous type of waste that Botswana grapples with as health care improves, but facilities for incineration and other types of waste management do not expand at the same pace. New types of waste such as face masks emerge due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Mining waste, which amounted to as much as 871 tonnes in 2018, is another type of hazardous waste, which Botswana deals with at a time when landfills are not expanding at the same pace as the growth in mining output. Additionally, the country’s diamond mining sector, which is pivotal to its economy, also has huge environmental footprint. The mining process leaves large swathes of land exposed due to the removal of vegetation, and this can lead to soil erosion with the loss of soil nutrient layer. Its associated airborne dust that includes toxic chemicals has also been blamed for environmental and human health issues. In addition, the diamond mining uses large volumes of water in the mining and processing stages. The World Health Organization’s reports show in Botswana, air pollution accounts for 40 per cent per cent of an estimated 330 child deaths due to acute lower respiratory infections (WHO, 2016). The country’s pockets where the quality is poor especially include urban and mining areas. For example, pollution levels in Gaborone reaches as high as 216 micrograms per cubic metre with much of the pollutants coming from construction work, open burning of waste, and coal fired industrial activity and rail transport. Seasonal dust storms from the Kalahari sands are also common. With increased industrial activity and growth in urban population, outdoor air pollution levels in urban and mining areas are set to remain high in these areas. Indoor air quality is generally poor across the country due to the high dependency on fossil fuels for cooking, heating, and lighting in poorly ventilated homes. A national average of 37 per cent households use fossil fuels with the situation being more severe in rural areas where 65 per cent households depend on this form of energy. With as much as 2,300 deaths per year attributable to indoor pollution, the country’s key legislation against pollution, including the Atmospheric Pollution Prevention Act and the Environmental Impact Assessment Act do not seem deterrent enough to stop or reduce the number of people dying from acute respiratory illnesses.

|

While urbanization reflects an expanding and industrializing economy, Botswana still grapples with providing all its residents with basic services such as safe drinking water, clean cooking fuels, and electricity, among other amenities which could play a vital role in curbing pollution and waste. As the country’s population increases, the volume and complexity of waste produced also grows driven by the growth in and densification of urban areas, changing consumption patterns, industrialization, technology advancements, economic growth, and the consequent rise in incomes. Unmitigated, these dynamics threaten the country’s human health and wellbeing, with negative outcomes on public expenditure and labour productivity. Though Botswana has managed to keep slum settlements to a minimum, but waste management is a challenge across many parts of the country, with urban areas generating four to seven times more than rural areas. Even with their low waste generation rates, collection levels are exceptionally low in rural areas, while urban areas continue to be faced with outdoor air pollution from industrial and transport operations. Governmental reports show about 14 per cent of waste is collected in rural areas, while in the country’s urban areas, waste collection has been on the decline, with 81 per cent of waste collected in 2001 compared to 76 per cent collected in 2011. The amount of electronic waste generated in Botswana has increased from a per capita average of 2.83 kg per year in 2000 to 7.92 kg per year in 2019. Hospital waste which averages 0.1 kg to 0.75 kg per patient is a hazardous type of waste that Botswana grapples with as health care improves. Facilities for incineration and other types of waste management do not expand at the same pace, even with the emergence of new forms of medical waste associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, radioactive waste remains another cause of concern in Botswana, albeit being at low levels. Sectors that generate radioactive waste in Botswana include agriculture, construction, hospitals, industry, mines, and research facilities. Mines and hospitals have spent sealed radioactive materials that they use for various operations. The country’s Waste Management Act, Botswana Clinical Waste Management Code of Practice, and Miners and Minerals Act are not adequate for the handling of new types of waste, as well as not deterrent enough to stop bad practices such as waste burning. This is in addition to weak enforcement of other existing waste management policies. Current practices such as those prevailing in Ngamiland West where 50.89 per cent of waste is burnt do not just continue into 2030, but also spread to other areas.

![]()

![]()

| _ |

|

Solid and liquid waste management are regulated under the Waste Management Act 1998. The government recognises that there is a direct correlation between sanitation, health, and human and environmental well-being. Against this background, it is keen to ensure that the level of cleanliness in the cities and rural areas is maintained through the prudent management of solid and liquid waste as stated in its national development plan. A targeted response to these urbanization challenges will inevitably aid in the attainment of the sustainable cities SDG. Considering surging medical waste attributed to COVID-19 and other healthcare issues, Botswana "s government response has been to enhance regulatory interventions in the sector using existing Botswana Clinical Waste Management Code of Practice 1996 and Waste Management Act 1998. Her authorities advocate for safe and sustainable collection, transport, treatment, and disposal for all healthcare waste, including liquid and chemical waste. There, however, remains a strong need for a law that clearly defines roles and responsibilities for healthcare personnel responsible for the handling and disposal of the waste streams at the point of generation at health care centres; and, to formulate a more robust healthcare waste management system. Chemicals are managed under the Chemicals Safety Guidelines and there are plans to address the deficiencies in this sector in the national development plan. Some of the activities as specified in the Botswana s 11th National Development Plan (NDP11) include its need to develop and implement a national chemicals strategy and management plan, as well as the adoption and domestication of the relevant environmental conventions on chemicals and waste management. This is in addition to exploring modalities for public private partnerships for the management of chemicals treatment and disposal facilities, including in the development of hazardous waste treatment and disposal facilities. Also, as a show of increasing action for curbing radioactive waste, the number of registered sealed sources in use in Botswana continues to increase, and by August 2020 stood at 650, according to the Botswana s government. The number of disused or spent sealed sources stored at end user s facilities is decreasing, albeit slowly, as end-users continue to make efforts to return their disused or spent sealed sources to the manufacturer or supplier as required by law. Other institutional frameworks being employed in Botswana to curb pollution and waste include the following: • Section 65 of the Mines and Minerals Act requires permission to mine through a mineral concession or permit, that includes a comprehensive Environmental Impact Assessment as part of the project feasibility study report. If approved, the environment management plan submitted in tandem is followed to ensure enforcement and compliance with the mining industry standards. The Act also requires the developer to minimize and control waste to cause negligible damage to human health and environmental resources and to treat pollution and environmental contamination events immediately. • The Atmospheric Pollution Prevention Act 2008 and the Ambient Air Quality - Limits for Common Pollutants of 2012 published by the Botswana Bureau of Standards aim to prevent air pollution from industrial activities including mining; and requires the developer to be in possession of an air pollution registration certificate especially if the activity occurs in a controlled area. • In terms of managing radioactive waste, Botswana s legal framework is guided by the Radiation Protection Act of 2006 and its Regulations of 2008 which are both under review. The institutional framework for radiation management includes the Radiation Protection Board and the Radiation Protection Inspectorate.

|

With a growing population and high urbanization trends, Botswana has an opportunity to inculcate robust circular economy interventions. This includes expanding and modernizing the existing waste management infrastructural facilities such as the collection, transportation, and recycling systems to cope with increasing amounts of wastes being generated into 2030. Evidence-based interventions to stimulate public-private partnerships would also play a central role in not only managing wastes at urban and industrial levels, but also pollution including in the energy and transportation sectors. This is in addition to creating a fair playing field for the involvement of informal waste pickers, especially for recyclable material such as glass, paper, and some plastics. Similarly, and with a view to stemming the tide of air pollution at household and other levels, the country is well-placed to increase investments that would expand the adoption of clean cooking and lighting systems. Botswana also has good opportunity to develop a robust chemical waste management programme, coupled with establishment of wide-ranging legal and institutional frameworks to regulate domestic and industrial chemicals be developed and operationalized. Sound management of chemicals and waste is critical to sustainable health and to support good quality of life and enhance biodiversity. Actions to mitigate pollution and implement solutions should be urgently undertaken.

|

Botswana has a physical shortage of water, receiving between 250 - 650 mm/year of rainfall while evaporation rates are as high as 1,900 - 2,200 mm/year. Over 44 per cent of the country’s population lives under conditions that are described as water stress, water scarcity and absolute scarcity (World Data Lab, 2020). With only 96 Mm3/year of sustainable aquifer yield and 73.2 Mm3/year that can sustainably be withdrawn from surface water sources such as dams, Botswana’s total sustainable yield of water is 169.2Mm3/year against demand of 200 Mm3/ year. Classified as semi-arid and arid, and receiving an average of 250 mm of rainfall per year in the southwest, and about 650 mm in the north, Botswana is prone to severe droughts and episodes of flash floods. High evaporation rates of 2,200 mm per year result in the country having low rates of groundwater recharge and surface runoff. Average annual rainfall has also been decreasing across much of Botswana, while average temperatures are warming. Going into 2030, the country continues to have a water availability challenge. The situation is not helped by the low aquifer recharge across much of the country as this reduces the amount that can sustainably be withdrawn from aquifers in future. Through good investments in the water sector, as much as 99.5 per cent and 83.5 per cent of the population in urban and rural areas, respectively, has access to safe drinking water. Going into 2030, the country achieves universal access to safe drinking water although many still depend on shared communal water sources. The country’s perennial rivers are all transboundary and shared with neighbouring countries, and they include the Limpopo, Okavango, Zambezi, Orange-Senqu and Shashe-Limpopo. The availability of water to Botswana from these perennial sources is not only limited by the regional instruments for the transboundary management and sharing of resources such as the Revised Protocol on Shared Watercourse Systems, but also by the farther distance the rivers are from key users and major settlements. As of 2017, Botswana had a national average of 60 per cent access to sanitation services, with a huge disparity between urban and rural access. Only 39 per cent had access in rural areas while 75 per cent had access to sanitation services in urban areas (UN Water; WHO, 2018). Without policy coordination between the Water Act, which provides for the infrastructure to deliver water, and the Public Health Act, which covers sanitation, Botswana’s ratio of population using safely managed sanitation services and hand washing facilities does not meet the country’s targets under both the SDGs and Vision 2036. In addition, the country fails to reduce the ratio of people practicing open defecation, which was recently as high as 33 per cent in the rural areas. According to recent data using a stricter definition of access to services adopted by the SDG targets and indicators, in Botswana, 90 per cent of the population had access to ‘at least basic’ services for drinking water. While there is no information on the access to ‘safely managed’ services, data reveals that 79 per cent of the national population had water on their premises, with a significant gap between the urban population (93 per cent) and the rural population (47 per cent) (UNICEF; WHO, 2019). Similarly, among the total number of households with access to improved water through a piped or tapped water source in 2011, 65 per cent resided in towns and urban villages, while 35 per cent of the households were in rural villages. In 2017, about 73 per cent of households in towns and urban villages had access to a piped or tapped water source while only 27 per cent of households in rural villages had access to a piped or tapped water source. These results also highlight that even though there was an increase in the number of households with access to piped or tapped water source in towns and urban villages, rural villages incurred a decrease (Statistics Botswana, 2020).

Refrences

AfDB. (2014). Botswana Country Strategy (2015-19). Abidjan:

African Development Bank (AfDB). https://www.tralac.

org/images/docs/6879/botswana-country-strategy-paper-2015-2019.pdf

AfDB. (2020). 2018 African Economic Outlook: Botswana

Abidjan: African Development Bank (AfDB). Retrieved

from https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/

Documents/Generic-Documents/country_notes/Botswana_country_note.pdf

BIDPA. (2008). The progress of good governance in Botswana.

Gaborone: Botswana Institute of Development Policy

Analysis (BIDPA) and UN Economic Commission for

Africa (UNECA). https://media.africaportal.org/documents/Progress_of_good_governance_in_Botswana_2008_1.pdf

Calleja, R., and Prizzon, A. (2019). Moving away from aid: The

experience of Botswana. London: ODI. https://odi.org/

en/publications/moving-away-from-aid-the-experienceof-botswana/

In Botswana, climate change manifests itself in the form of increased variability of key climate elements such as temperature and rainfall, and through an increase in the frequency and severity of extreme events such as heat waves, destructive rainfall, flash floods, and droughts. The main concerns for Botswana are increased energy and water stress because of rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns, losses in rangeland productivity and reduced agricultural yields which are profoundly threatening food security.

UNEP reports of 2021 on Botswana’s state of environment for temperature trends over the last several decades indicate that it has experienced a considerable increase in temperature over recent years. An analysis of climate data from 1970 to 2015, for instance, shows an average rise of temperature by around 1.5°C. Rainfall is highly variable in time and space. Rainfall variability is an important feature of semi-arid climates, and climate change is likely to increase that variability in many of the regions of Botswana. The average annual rainfall for Botswana is approximately 405 mm, while the mean number of wet days is around 53. Trends for annual average rainfall across Botswana indicate a general decline (Nkemelang et al., 2018).

Projections from Botswana’s Ministry of Environment and Tourism shows by 2050, most of the country will experience high average temperatures of 25°C to 26.9°C, thus the country will be hotter than relative baseline temperatures. Figure 3 and 4 illustrates historical annual mean temperatures and temperature projections for 2050 using Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) values - RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5.